Think the flush toilet was a welcome improvement in sanitation back when cesspools and outhouses were the norm? Not exactly. In the 1800s, flush toilets were quickly dubbed public enemy number one by those concerned about public health and clean water. Overflowing cesspools, polluted rivers, cholera epidemics, and god-awful smells were the consequences of the newly popular water-flush toilets — aka water closets or WC. Plus, these toilets diluted the nutrients in human manure — a problem for farmers since synthetic fertilizers had yet to be invented. Leaders and inventors across Europe sought ways to transform human feces into a resource, without compromising human health.

Everyone, it seemed, had an opinion (or complaint) about the sewage mess. As Darwin published his theory of evolution and railroads first crisscrossed the English countryside, The Sewage Question loomed large in public debate: “What is the cheapest and most efficient technical process for rendering human excreta useful instead of dangerous?” wrote Frederick Charles Krepp in 1867 in his treatise on the subject.

Many wanted to reuse human manure, called night soil, in agriculture. This had been a common practice until fast-growing cities and water-flush toilets overwhelmed the existing reuse systems. New understanding of soil science highlighted the need to replenish nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil, but how? Farmers turned to the morbid practice of using ground-up human bones, rich in phosphorus, dug up from battlefields. When bones ran dry, nitrogen-rich bird guano, imported from South America, filled the gap. But in just a few decades, guano supplies dwindled.

Everlasting Soils and Edo, Japan

Fertile soils in China and Japan inspired Europeans: There, returning human nutrients to the land was woven into the culture, from customs to religion, from government edicts to organized guilds that transported the city’s excreta to the surrounding countryside. European visitors to cities like Edo, Japan (now Tokyo) were impressed by the cleanliness of the streets, the clean water, and the widespread reuse of excreta. But, unsurprisingly, nobody liked the smell from the manure barges leaving the city each day, full of rich and stinky human manure.

It was called shimogoe in Japanese, meaning “fertilizer from the bottom of a person.” And Edo had many bottoms, a population of around a million by the early 18th century — nearly twice that of London at the time. Japanese farms thrived when nutrients taken from the land in the harvest were returned to the fields as manure, a practice widespread as early as the 12th century.

Toilets in Edo were located away from the living space — a simple pit with a platform and a hole so a person could squat over them. Urine was collected separately, in jugs or barrels, and also used for fertilizer.

At first, farmers traded directly with toilet owners — they exchanged vegetables for the poop. Over time, fertilizer prices skyrocketed and a trade association formed to buy and sell the manure for silver. Collectors paid to empty toilets and transport the poop outside of the city, where they sold it to farmers. At the farm, it was fermented (composted) and used to grow crops, which were later sold back to people in the city. And so the cycle continued. Records even show disputes over the rights to collect poop from desirable neighborhoods, and, on occasion, theft.

Inspired by Asia’s success, European toilet inventors looked for a suitable way to collect night soil and spur an economy around it. Many of their schemes and inventions appeared money motivated, they wanted to get rich selling sh$t, but not all. Enter Reverend Henry Moule, an accidental toilet inventor who tackled the Sewage Question out of a desire to save lives.

For Healthy People and Rivers, Use a Dry Earth Closet

The horror of cholera — a disease that could kill within a day — turned Reverend Henry Moule of Fordington, England, into a toilet inventor. After two cholera epidemics in 1849 and 1854 cut through his rural parish, he swore off the “evil” flush toilet and filled in his family’s cesspool. He wanted to “cut the evil off at the source” and recycle human nutrients.

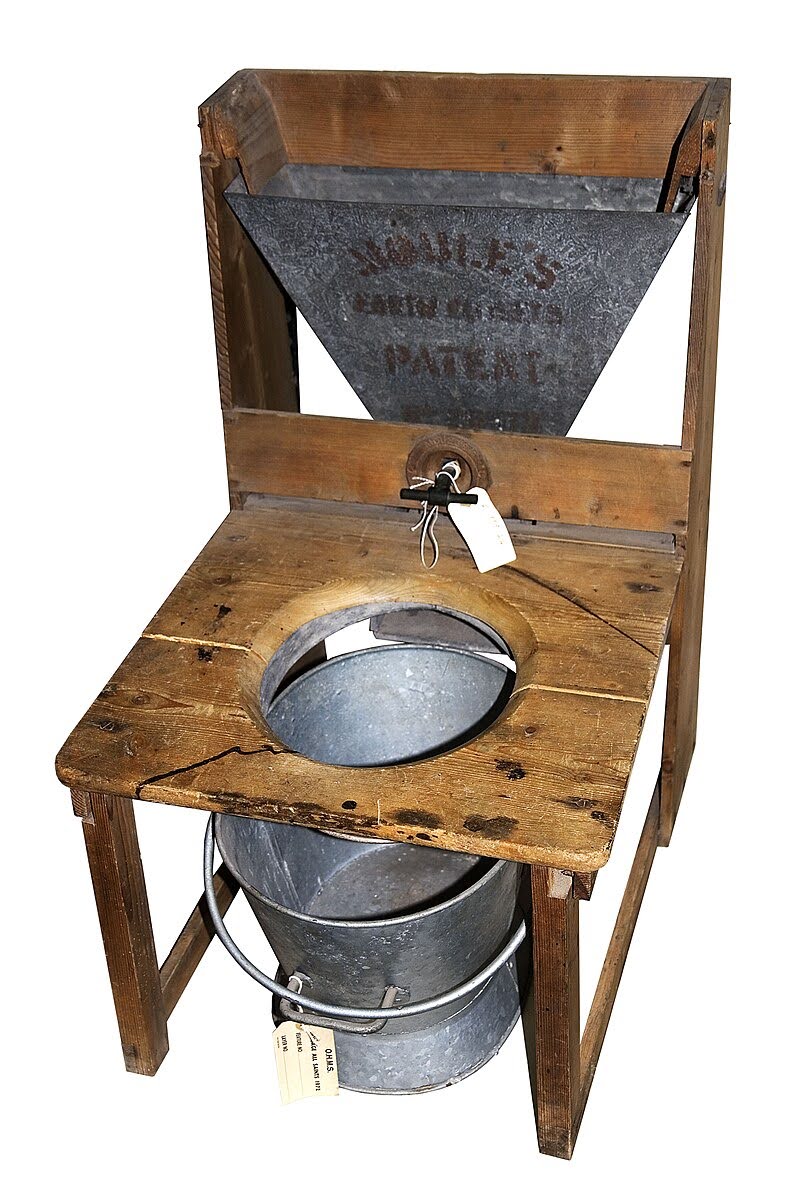

Moule developed a simple design — a toilet that flushed with dry earth. The toilet seat sat above a pail, and a hopper full of dry soil replaced the tank of water used in a flush toilet. After use, a “flush” of dry earth covered the material, preventing odors. Once full, the pail contents were buried, and soil microbes would transform the excreta into compost. Moule discovered his vegetables grew luxuriantly in the compost — peas six feet tall — impressing his neighbors and local farmers.

To make it easier for other people to use his design, Moule formed a company to manufacture and sell the dry earth closet. They became wildly popular all over Great Britain, in the United States, in India, and beyond. They were used in hospitals, schools, prisons and even in Queen Victoria’s Windsor Castle.

Despite all its simplicity, servicing a dense city with this technology would require a whole lot of wagons rolling through neighborhoods, day in and day out, delivering dry earth and collecting humane manure. That’s why city engineers pooh-poohed the earth closet as just a small-town solution.

This Toilet Rocks — Like a Hurricane

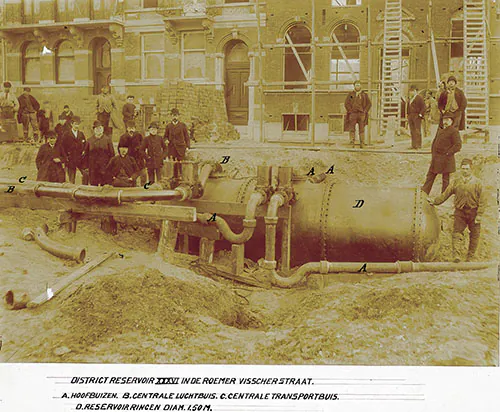

On the other side of Europe a totally different style of toilet emerged. Called a “pneumatic air toilet,” they were installed by the thousands in cities like Amsterdam and Prague. Designed for urban areas, this technology was cheaper and easier to install than a standard gravity flow sewer. Plus, air toilets didn’t need wagons to haul dirt or manure to every house. Air toilets prevented bad smells and preserved the fertilizing potential of the city’s excreta. Many sanitarians were certain this was the solution to The Sewage Question.

Invented by the Dutch-born engineer, Charles Liernur, a self-taught and ambitious man. Liernur’s cradle-to-grave sewer design was unique among the slew of competing technologies, earning him a knighthood from the emperor of Austria-Hungary. Liernur described his design: “My method deals with faecal matter from the moment it is produced until the moment it is put under the ground, for stimulating useful vegetable life.”

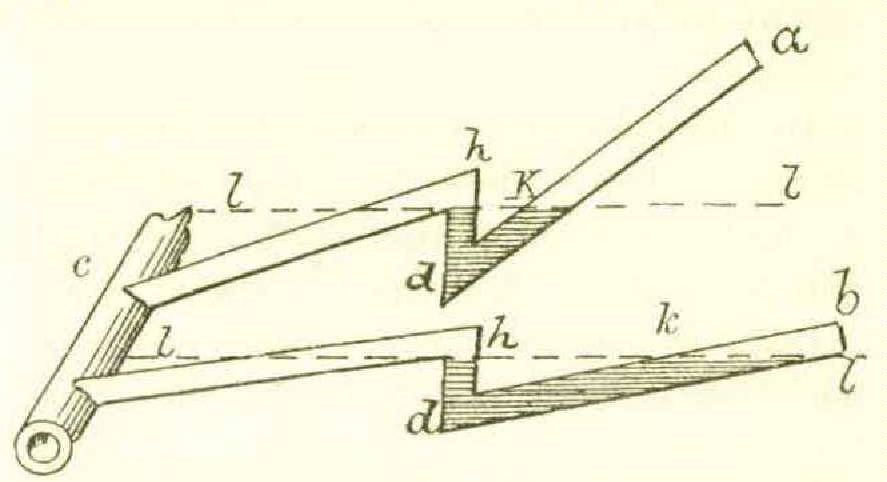

The indoor toilets were nothing special — a seat above a sloped pipe, which dropped into a larger chamber. Both pee and poo fell into the chamber, without any flushing. The toilet lid was sealed with a rubber gasket to prevent odors from entering the house. House toilets were separated from the rest of the sewer system by an air-tight valve in the pipes outside the house, near the street.

A town was divided up into groups of 100 or so houses, all connected via the sewer pipes to a large, buried tank. Each night, a team would service the neighborhood using a mobile steam engine pulled by one horse. To begin the sewage removal process, they sucked the air out of the buried tank and the sewer pipes running to each home. This created a negative air pressure inside the sewer system, all the way up to the valve outside each house.

Next, workers would open and close each valve, house by house. Opening the valve released the atmospheric air pressure in the home toilet, which was much higher than the air pressure in the pipes. The pressure difference caused the air to shoot into the main sewer, with hurricane force, shoving pee and poo inside the toilet chamber out of the house and into the city sewer. The force was so powerful that solids, liquids, odors, flies, an old shoe or whatever got thrown down the toilet, was “hurled into the street reservoir as if by magic.”

After all the house toilets were emptied and the street reservoir filled, the team pumped the below-ground tank’s contents into their mobile container, then moved to the next neighborhood. In this fashion, a team of three people could service 10,000 residents per night.

At the end of the night, teams took the slurry to a central depot and piped it into wooden oak barrels. Air and water-tight, the barrels were transported by railroad or steamboat to farms and fields. There, they’d attach it to a plough-type device that injected the nutrient-rich slurry into the root zone of plants.

The pneumatic sewerage system did not replace the water-flush toilet, as advocates dreamed. But it did inspire modern technology: Liernur’s toilet was a precursor to vacuum toilets (used on airplanes) and vacuum sewers (used in areas unsuitable for conventional sewers).

What sewage question?

The Sewage Question was never settled in 19th Century Europe. After German chemists discovered how to take nitrogen straight from the air to make synthetic fertilizer (a process that uses lots of fossil fuels) in the early 1900s, and profits from selling poop fell short, the push to recycle human nutrients faltered. The question became: “What’s the cheapest way to get rid of this sh*t?” The answer: Dump it into rivers and the sea. Let the nutrients pollute. Rely on synthetic fertilizers.

In the long run, polluting the water and the planet comes at a steep price — environmentally and financially. Think climate disasters, loss of fisheries, the global sanitation crisis, and paying for water treatment, pollution cleanup, and public health interventions. Perhaps now is a good time to return to The Sewage Question. Taking inspiration from the past, let’s find 21st-century systems to recycle nutrients in human manure while protecting people and the planet.

Laura Allen is a writer and educator based in Oregon. She co-founded Greywater Action, where she teaches people how to transform their homes to reuse water. She authored the books, The Water Wise Home: How to Conserve, Capture and Reuse Water in Your Home and Landscape, and Greywater, Green Landscape. Her article, For a better brick, just add poop, won the Gold Award in Children’s Science News from the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Awards (2023). Her favorite pastimes include gardening, hiking, reading and visiting eco-toilets.