Under dappled sun and fragrant cedar, the landscaping at Rush Creek Lodge blends into the surrounding forest. Here, native plantings restore the hillside that was disturbed during construction of the lodge, bringing beauty, feeding pollinators and cleaning the air – all without consuming much water. This is possible thanks to greywater– that is water previously used in showers, sinks or washing machines. Even during times of drought, this large landscape will stay hydrated since the irrigation water is first used in the hotel showers, then flows out to the plants. The greywater systems also model a smarter way to design buildings.

Rush Creek Lodge sits right outside Yosemite National Park in California, and guests who come to relax and enjoy the beautiful scenery might not notice anything different about their rooms – like how their slightly dirty shower water swirling down the drain goes on to irrigate the landscape. But signs inside and out teach them about this simple reuse system.

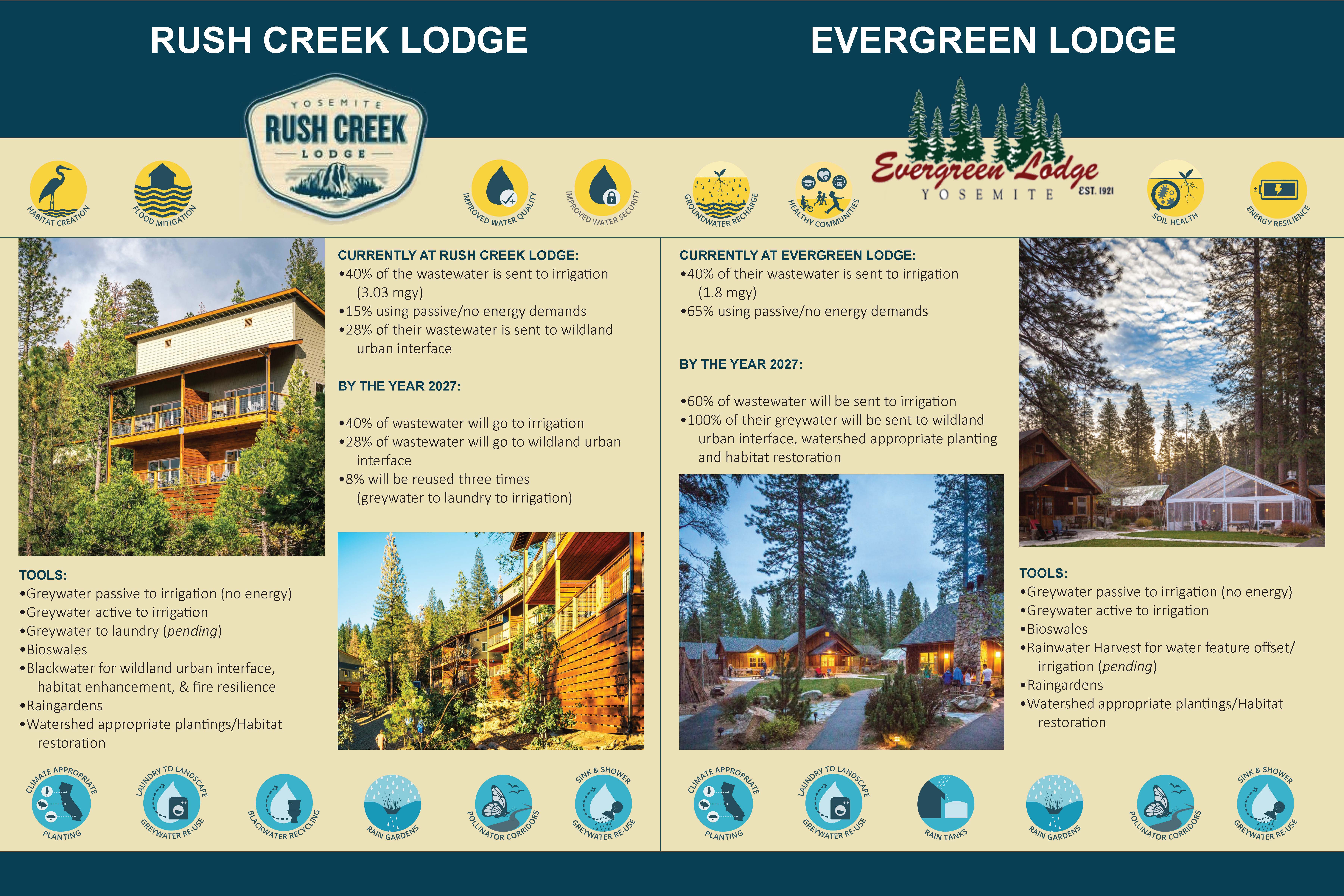

This lodge employs both low-tech greywater irrigation systems using gravity and wood chips to process the water, as well as more complex wastewater recycling systems that treat all wastewater. Overall, more than three million gallons of water are reused each year, cutting back on groundwater pumping and saving energy. Treated wastewater is pumped to the edge of the property to create a hydrated strip of vegetation between the unirrigated forest and the buildings.

As they envisioned the new lodge, owners Lee Zimmerman and Brian Anderluh planned to reuse water. They had first-hand experience with greywater at another lodge they own, Evergreen Lodge, located a few miles down the road.

Cabin-sized greywater systems

Back in 2010, the company Watershed Progressive installed the first commercial-sized greywater system in the county at Evergreen. There, cabins and commercial dorms and laundries reuse 1.8 million gallons of greywater per year through both simple, gravity-flow systems as well as pumped and filtered systems. The majority of the buildings at Evergreen Lodge are small cabins, with one or two guest rooms in each. Over 50 of these cabins were converted so the showers flow by gravity to irrigate landscaping around the cabin.

These cabins are similar in size to a residential home and yard, and the system can be replicated for houses, points out Regina Hirsch, the director of Watershed Progressive and designer of these systems. For the past 15 years, Evergreen’s greywater systems have run year-round, over snowy winters and hot summers, and the plants are thriving.

“Greywater is one of the tools in the [sustainability] toolkit,” says Hirsch. She designs systems that take advantage of all the water that comes onto a site, be it rainwater or wastewater. Other systems in this toolkit are rainwater collection, rain gardens that soak up roof runoff, and native plantings. “I can’t speak highly enough of the benefits of these tools,” she says. They help with habitat creation, flood protection, and improved groundwater recharge. Also, greywater can improve soil health, and processing our wastewater helps us be more energy resilient, she says.

These systems are also teaching tools. Hirsch helps organize an annual conference, called Localizing California Waters, often held at Rush Creek or Evergreen Lodges. This conference connects people working for resilient communities through collaboration and “the power of small actions to build a better world.”

Regulations: helpful or not?

Reusing greywater is an untapped resource in most buildings. Why? In some states, regulations prohibit it. But in other places, even with supportive regulations, a lack of experienced designers or installers makes it hard for an interested building owner to find the support they need. Cost is another barrier. In some buildings, it's easy to tap into greywater pipes to install a system, but in other buildings the pipes may not be accessible, for example if they’re buried in a concrete slab. Complicated retrofits may drive costs up too much.

That’s why planning a greywater system during the design and construction of a building is typically the most affordable option, like at Rush Creek Lodge. Some cities, like Los Angeles, California and Tucson, Arizona, have made laws in attempts to keep greywater systems more affordable. These laws require new buildings to install what’s called “greywater-ready plumbing,” which is essentially separate pipes to take greywater outside the building for a future greywater system to tap into.

The future of greywater

As greywater systems become more familiar, with their benefits and challenges better understood, regulations can evolve to adequately protect public health and conserve water resources. A handful of states have revamped their rules, but most states still lack them.

States and cities can look to existing codes available for guidance, such as in IAPMO’s Water Efficiency and Sanitation Standard (We-Stand). This standard covers all types of alternative water, including greywater, as well as offers guidance on how to safely and affordably require greywater-ready plumbing in new construction.

Back at the lodges, says Hirsch: “Every person who [visits] learns a little bit more about where their water comes from and where it’s going.” This helps them envision how buildings can be designed to reuse water in a simple way. And, she points out, “greywater is one of the best ways to look at how to mimic nature and get back to it.“

Laura Allen is a writer and educator based in Oregon. She co-founded Greywater Action, where she teaches people how to transform their homes to reuse water. She authored the books, The Water Wise Home: How to Conserve, Capture and Reuse Water in Your Home and Landscape, and Greywater, Green Landscape. Her article, For a better brick, just add poop, won the Gold Award in Children’s Science News from the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Awards (2023). Her favorite pastimes include gardening, hiking, reading and visiting eco-toilets.

.jpg)