- Whales feed deep in the ocean and poop at the surface, recycling nutrients back into the food web.

- Their waste arrives in summer, exactly when surface waters need fertilizing most.

- Even whale urine transports nitrogen across thousands of miles to nutrient-poor breeding grounds.

- Human sewage harms the ocean because it's concentrated, polluted, and dumped where those nutrients don't belong.

- Strong conservation laws have helped whale populations and ocean health recover.

The first time biologist Joe Roman encountered whale poop he was on a research boat off the coast of Canada. A right whale emerged from the water, its head covered with mud from feeding on the bottom of the bay. It surfaced to breathe, rest and digest, and just before diving again — it put out “a bunch of poop!” recalls Roman, in a plume nearly as big as his boat. His research, at the University of Vermont, now focuses on whale’s nutrient rich excreta. This whale poop — colored neon green, orange, or brick red — is a bounty for ocean life, unlike polluting human sewage.

In the ocean, nutrients tend to flow downward. That’s because algae grows at the surface, where the sunlight hits, but when it’s eaten by plankton and then fish, the nutrients move deeper into the water. As fish and other creatures eat, poop and die, the nutrients sink out of range of the light.

Whales reverse this flow. Roman refers to it as the “whale pump” — the movement of nutrients from deeper waters (where whales eat) to the surface (where they poop). This uplifting of nutrients is especially important in northern waters where whales feed each summer.

During the fall and winter in the northern oceans, winds churns the water, mixing nutrients around, yet little algae grows due to lack of sun. In the sunny spring, algae bloom, feeding zooplankton. Once nitrogen runs out, algae can’t grow and the waters become layered: nutrient-poor water on top of deeper nutrient-rich waters.

Enter whales. They come in the summer to feed and “that’s when it matters most ecologically,” says Roman. They dive down to eat, then surface to defecate, fertilizing the waters for more algae and phytoplankton to flourish, supporting the ocean food web.

“They’re something like gardeners in the ocean,” Roman notes.

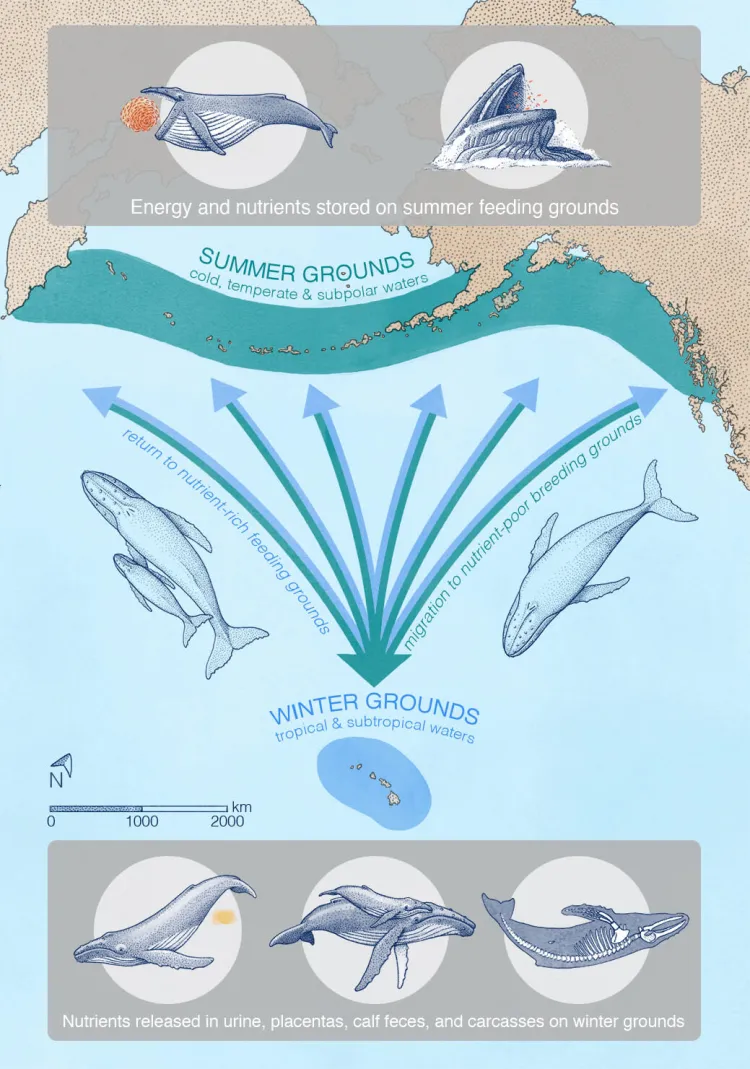

And some of these giant gardeners move across thousands of miles on their great migrations.

Whale wee

Last year, Roman and his team looked at how whale pee transports nutrients. Off the coast of Alaska, humpback and right whales fatten up in the nutrient-rich waters. Then they travel thousands of miles to their winter breeding grounds in warm, nutrient-poor southern water, for example, Hawaii or the Caribbean, where they breed and have babies.

Amazingly, whales don’t eat or poop during this time. But they still pee. They live off their blubber and release extra nutrients into their urine. Roman and his research team found that whale pee doubled the available nitrogen in their breeding grounds in Hawaii.

Right poop, right place

Overall, whale pee and poo boost the bounty of the ocean, so why doesn’t human excreta? A major reason, says Roman, has to do with how sewage enters the sea. It’s often released from a single place, like an overflow pipe, which dumps concentrated nutrients into one spot. Too many nutrients cause an overgrowth of algae, which need oxygen to grow. When they die, decomposers use oxygen, too. The end result is oxygen-depleted waters, devoid of life. Dumping human sewage into the ocean also introduces other pollutants, like chemicals, pathogens and micro plastics.

Also, the nutrients in whale excreta came from the sea. Whales cycle nutrients and disperse them across vast areas. Humans, on the other hand, eat from the land and discharge land-based nutrients into the sea, where they don’t belong.

Despite ongoing pollution issues, some things are getting better. Regulations such as the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act, along with community advocacy to enforce these laws, have improved life for sea creatures. “The difference is phenomenal,” says Roman. There are more whales, more fish, more sea birds and the water is cleaner.

This shift is important, says Roman, and cutting back on sewage and other pollution is essential to keep us moving in the right direction.

Laura Allen is a writer and educator based in Oregon. She co-founded Greywater Action, where she teaches people how to transform their homes to reuse water. She authored the books, The Water Wise Home: How to Conserve, Capture and Reuse Water in Your Home and Landscape, and Greywater, Green Landscape. Her article, For a better brick, just add poop, won the Gold Award in Children’s Science News from the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Awards (2023). Her favorite pastimes include gardening, hiking, reading and visiting eco-toilets.

.jpg)