- Waterless, container-based toilets offer a viable and often cheaper sanitation alternative for areas without sewer or septic access.

- Regulatory approval is often a bigger hurdle than the technology itself, requiring a shift in mindset from traditional water-based systems.

- This approach is highly adaptable, with potential applications for disaster relief, homeless communities, parks, and more.

When the fire tore through the Santa Cruz Mountains in August 2020, few people were thinking about their toilets. But once the ash settled and insurance money arrived, the cost of rebuilding came as another shock: required septic systems were so expensive that some homeowners couldn’t afford to rebuild at all.

Toilets were pricing people out of their homes.

A group of fire victims asked the county government about alternatives to traditional septic systems, which would cost anywhere from $60,000 to over $100,000 to install. Could they use lower-cost, waterless toilets instead? Compost toilets have existed for decades but county officials said no — California’s codes required a septic system.

So the group decided to push for change, seeking to legalize alternative toilet systems. Their efforts could benefit even more communities because the lack of sanitation options spans unhoused encampments, beaches, towns whose wastewater plants fail during disasters, and entire communities along the US-Mexican border.

The many benefits of container-based sanitation

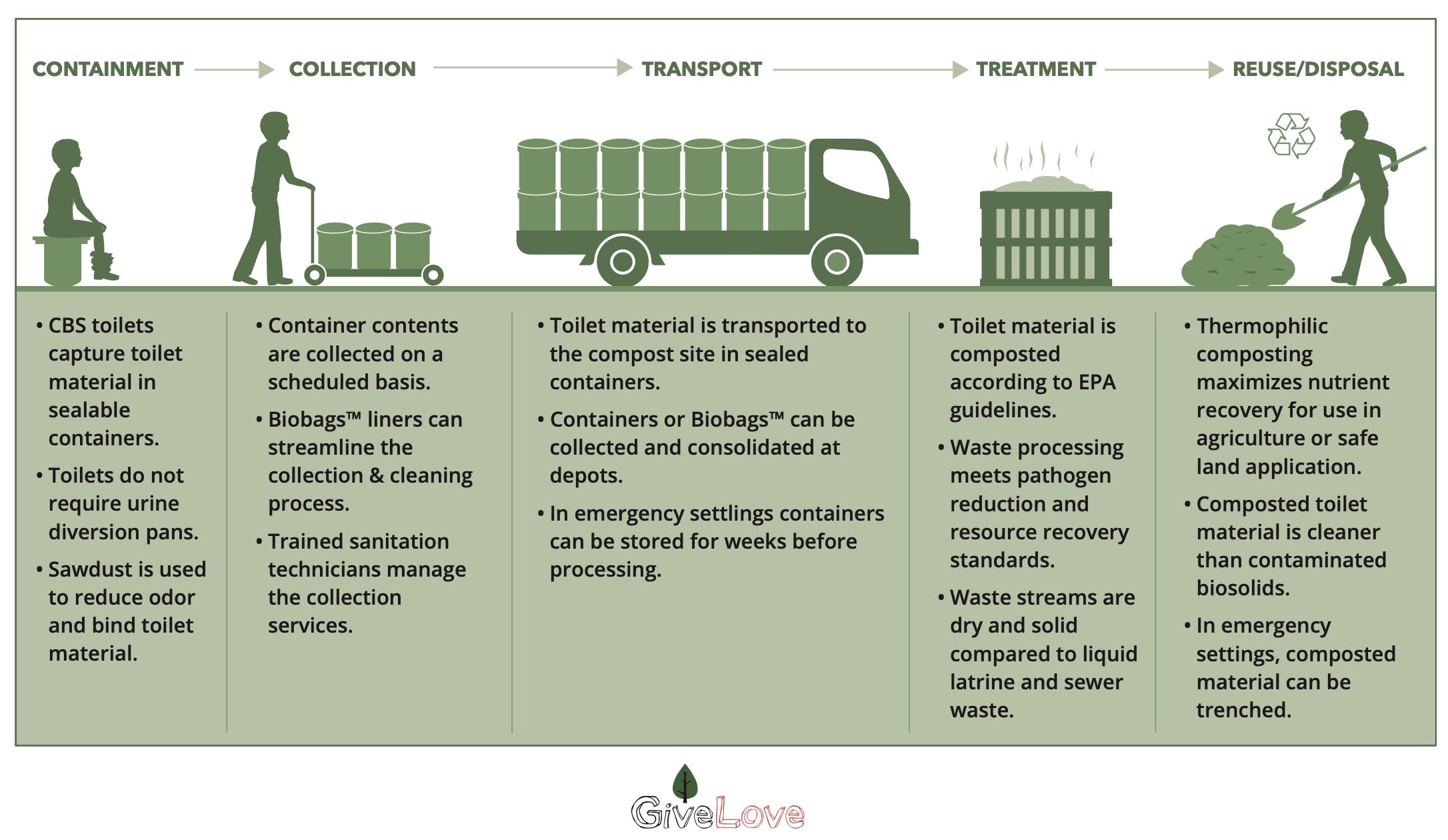

Wastewater professional Ryan Smith, who lived near Santa Cruz during the fires, had studied waterless, container-based sanitation systems for disaster preparedness while writing his thesis on homeland security. Container-based sanitation, or CBS, refers to systems that collect, transport and process human waste off-site in a safe centralized facility.

Smith teamed up with Alisa Keesey, a Santa Cruz–based nonprofit worker with GiveLove, which specializes in such sanitation projects. Together, with the support of County Supervisor Manu Koenig, they proposed a pilot program for Santa Cruz County. The idea was simple: provide fire victims with small portable toilets that collect waste in sealed containers. Once full, the containers would be swapped for empty ones and the material composted on the site of the local wastewater treatment plant.

This same type of system had already proven itself. After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which displaced millions of people, compost toilets “were the thing that was working in all that chaos,” recalls Keesey. And, she’d also seen how quickly such a system can be set up. When her team was asked to provide waterless toilets that wouldn’t freeze at Standing Rock during the pipeline protests, they designed and built enough toilets for 15,000 people in just three weeks.

But most county regulators remained skeptical. Delays and red tape stalled the pilot again and again.

A century of pail toilets in New York State

While container-based sanitation is rare in the United States, it has precedent. In 1908, the City of Syracuse, New York, launched a pail toilet collection service to protect Skaneateles Lake, the city’s drinking water source, from fecal contamination.

Hundreds of lakeside cabins lacked wastewater treatment, and officials knew any type of flush or pit toilet would pollute the lake, so they installed “privies”: toilet seats over removable metal pails. City workers collected full pails and replaced them with empty ones, much like trash collection today. The program lasted nearly 100 years before being phased out in the early 2000s — when the city funded the transition to compost toilets to replace the old system.

Toilets for unhoused camps and tiny home villages

Encampments of unhoused people often lack sanitation. Tawnya Mullen, an activist from Albuquerque, New Mexico, worked with a team of volunteers to set up a container-based sanitation program for such communities.

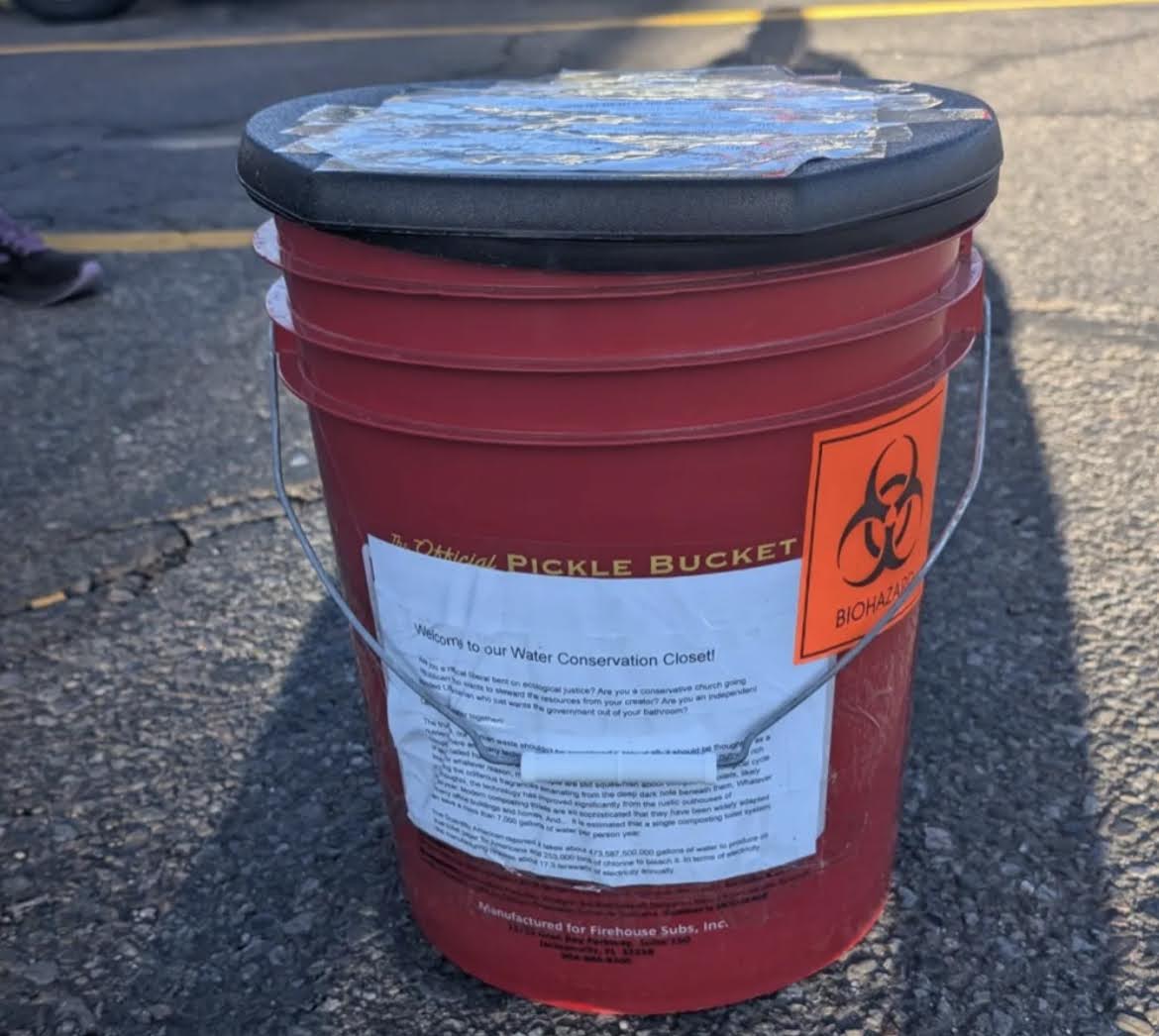

Last year, the team launched their pilot. For six months, they distributed bucket toilets, cover material and instructions, then regularly swapped full buckets for empty ones. “People were really happy to have sanitation access,” says Mullen. “Many took great care of the toilets.”

Still, challenges remained. Addiction, mental illness, and the transient nature of the camps made upkeep inconsistent. And, despite spending around a million dollars in 2024 on hazardous waste cleanup for human feces, the local government hasn’t funded the project. Yet, says Mullen, local politicians have expressed support for it, and she hopes for a funded program in the future.

In most places, integrating toilet pickup into existing waste collection services would be easy. “There's really no reason why this can't be part of any rational organics recycling program,” Keesey says. Portable toilets and sealed containers could also serve hard-to-reach or sewerless areas where people frequent — like beaches, bike trails or swimming holes.

A new mindset for sanitation solutions

Back in Santa Cruz, Keesey and Smith succeeded — after multiple revisions the pilot was approved! The hardest part, Keesey recalls, was convincing policymakers that this type of sanitation system could be done safely. Forging the legal path, says Keesey, took more effort than building the toilets and compost system.

“It takes a lot of persuasion to get people to look at infrastructure in new ways,” she says. And she believes this project made real progress.

.jpg)

Overall, says Smith, there are lots of things outside our control, but we can control our mindsets. For communities to benefit from container-based sanitation, regulators need to be open-minded, says Smith, and consider alternatives to using water as the primary method of managing human excreta.

Laura Allen is a writer and educator based in Oregon. She co-founded Greywater Action, where she teaches people how to transform their homes to reuse water. She authored the books, The Water Wise Home: How to Conserve, Capture and Reuse Water in Your Home and Landscape, and Greywater, Green Landscape. Her article, For a better brick, just add poop, won the Gold Award in Children’s Science News from the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Awards (2023). Her favorite pastimes include gardening, hiking, reading and visiting eco-toilets.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)