As climate change and population growth place increasing pressure on freshwater resources, the need for sustainable water management has never been more urgent. In a recent webinar co-hosted by OCTO Group (Open Communications for the Ocean) and the Ocean Sewage Alliance (OSA), Indigenous scholars explored a timeless practice: the circular water economy.

The webinar, featuring insights from Dr. Yolanda López-Maldonado (Yucatán, Mexico) and Dune Lankard (Eyak Athabascan, Alaska), showcased how Indigenous knowledge can guide contemporary water management. From the Maya’s ancient water storage systems to the Eyak people’s stewardship of Alaska’s Copper River Delta, Indigenous practices offer proven frameworks for sustainability. These systems are rooted in principles of reciprocity, community-led stewardship, and a deep respect for nature’s cycles.

Here are three key takeaways from the webinar that highlight the enduring wisdom of Indigenous water management and its modern implications:

1. Indigenous Water Management Is Decentralized, Community-Led, and Women-Centered

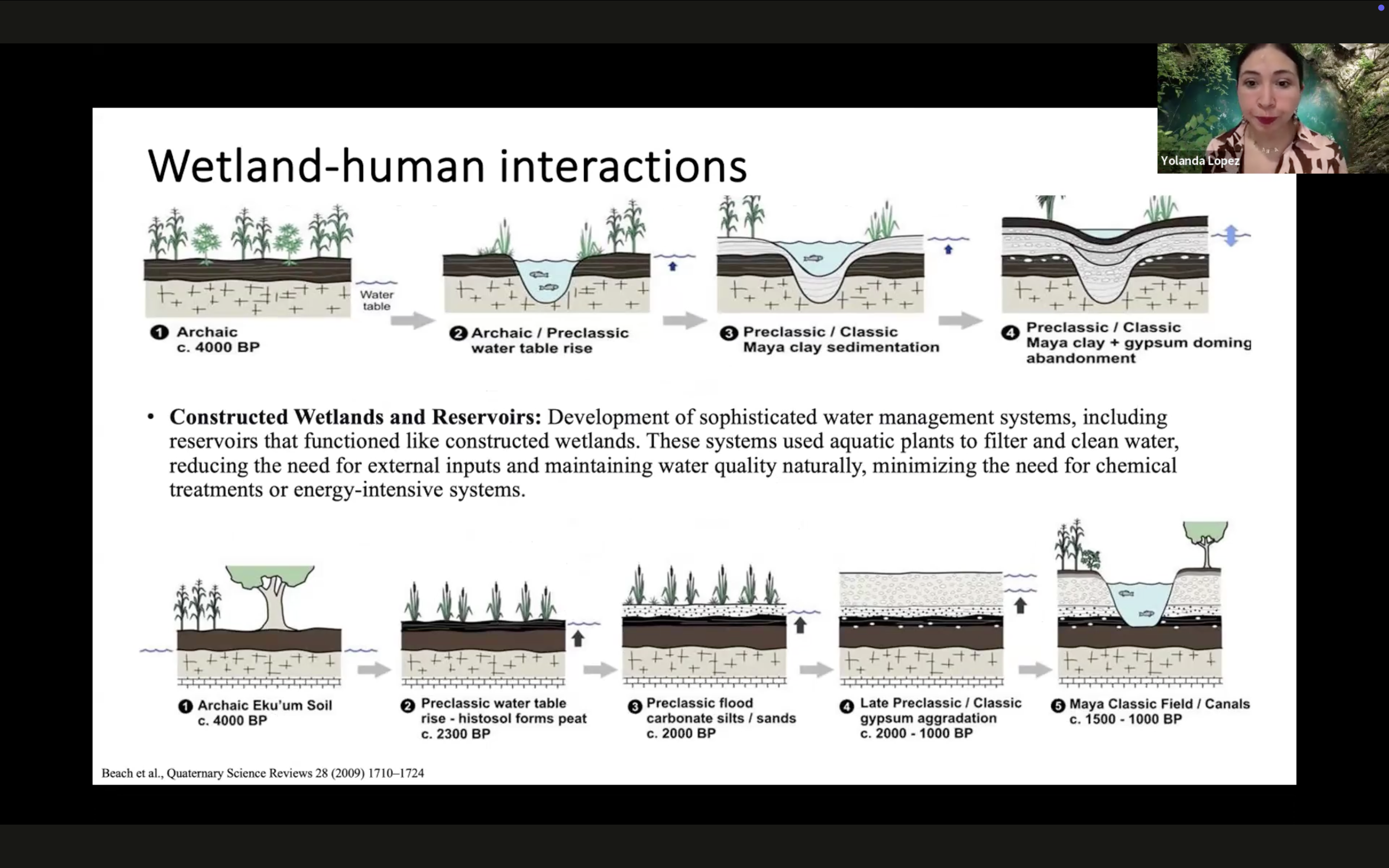

Indigenous water systems, like those of the Maya’s, were decentralized and community-driven. Locals managed their water resources, purifying water using natural methods like quartz and zeolite sand filtration and aquatic plants like water lilies. This approach ensured a reliable water supply and fostered a deep connection between communities and their environment. Dr. López-Maldonado points out that “indigenous communities have always planned for the future because we only take what we need from nature.”

A key feature of these systems was the central role of women, who often took responsibility for household water management. In many Indigenous cultures, women are the primary stewards of water, overseeing its use for drinking, cooking, cleaning, and agriculture. For example, Maya women in the Yucatán have historically managed household water needs while maintaining traditional practices that ensure water quality and sustainability. Their intimate knowledge of local ecosystems and water cycles makes them vital leaders in daily water use and broader community governance.

Dune Lankard, an Eyak Athabascan leader and advocate for regenerative ocean economies, highlighted the growing role of women in modern mariculture and kelp farming. He noted that 60 percent of new mariculture farmers globally are women, and their involvement is transforming some coastal communities. Women are at the forefront of preserving traditional food sources, restoring ocean health through practices like kelp farming, and building regenerative economies that empower coastal communities. As Dune emphasized, “If women and youth get involved in this industry, the men will follow.” This shift underscores the importance of women’s leadership in both traditional and contemporary water and ocean stewardship.

"This is one of the best presentations I have ever seen and heard." – Mahealani Scirocco, USA

Western water management can learn from this model by prioritizing local involvement, ecosystem health, and women's leadership. By allowing communities to take an active role in water stewardship, we can create sustainable systems that honor the interconnectedness of people and nature.

2. Two-Eyed Seeing: Bridging Indigenous and Western Science

The concept of “two-eyed seeing” — integrating Indigenous knowledge with Western science — is essential for solving complex environmental challenges. Dr. López-Maldonado emphasizes the need for diverse knowledge systems to address issues like climate change and water scarcity. This approach doesn’t just combine two perspectives; it creates a richer, more holistic understanding of the natural world.

For decades, Indigenous communities have taken the initiative to learn and navigate Western science, often out of necessity. Many Indigenous scholars and leaders have trained themselves to speak the language of Western science, using it as a tool to advocate for their lands, waters, and rights. For example, Dune highlighted how his community became citizen scientists after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, using Western scientific methods to protect their homeland and hold corporations accountable. This adaptability demonstrates the strength and resilience of Indigenous knowledge systems.

"Thank you so much for sharing such important presentations and experiences, and particularly for being a vehicle of inspiration and wisdom." – Jose U., Nicaragua

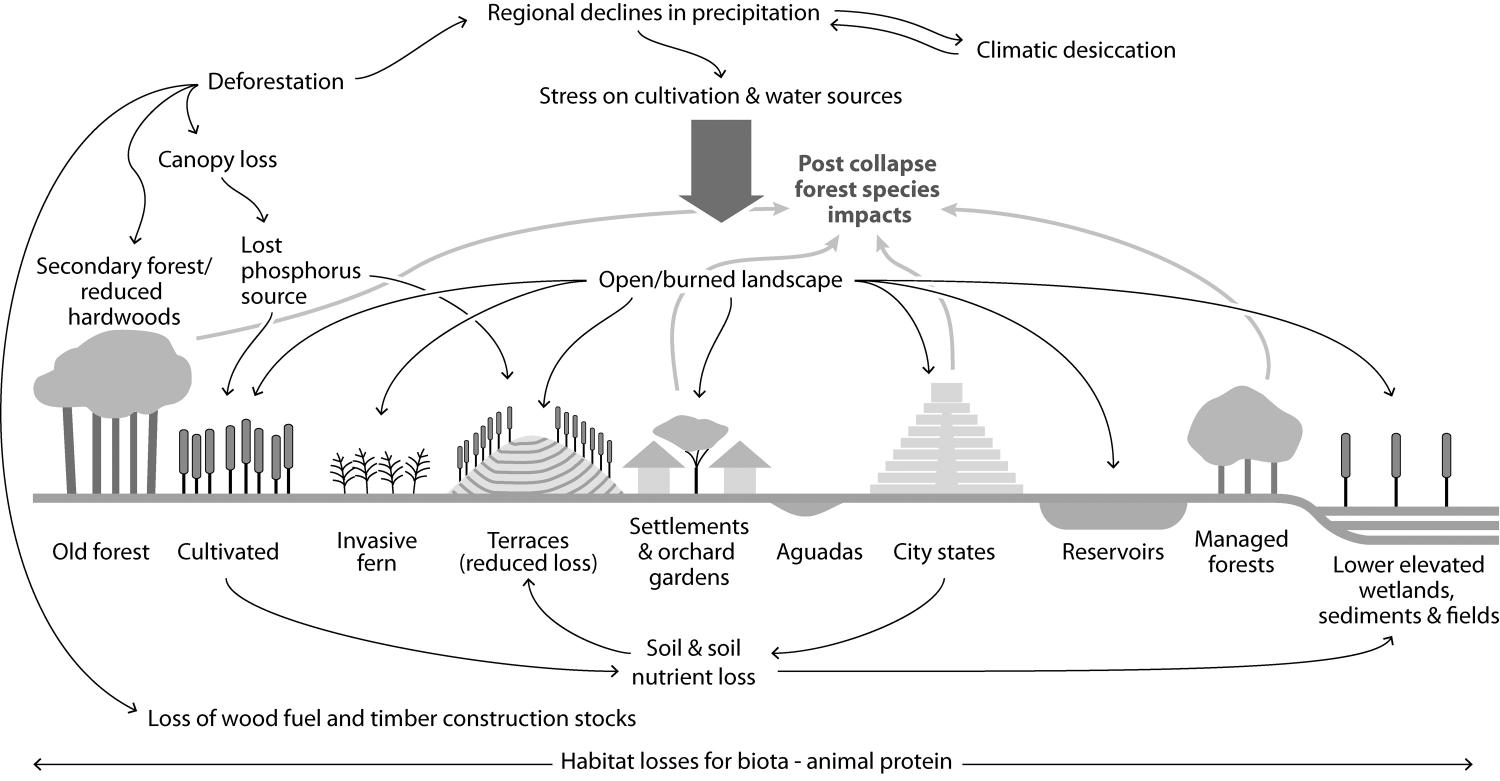

However, the responsibility now lies with Western science to fully engage with Indigenous ways of knowing. This means not only acknowledging the value of traditional ecological knowledge but also understanding the broader cultural, practical, and spiritual languages of Indigenous peoples. Indigenous knowledge is not just about data or techniques; it’s rooted in a worldview that sees nature as interconnected, sacred, and alive. For instance, the Maya’s water management systems weren’t just about engineering — they were tied to spiritual practices, community ceremonies, and a deep respect for natural cycles.

To truly embrace two-eyed seeing, Western science must move beyond token inclusion and create spaces for genuine dialogue and collaboration. This means centering Indigenous voices in research, policy, and decision-making, and recognizing that Indigenous knowledge is not “alternative” science — it is science, honed over millennia of observation, experimentation, and adaptation. As Dr. López-Maldonado noted, complex problems like climate change and water scarcity cannot be solved by narrow, single-discipline approaches. They require integrating multiple knowledge systems, including the spiritual and cultural dimensions that Indigenous peoples bring to the table.

By bridging these concepts, we can employ solutions that are not only effective but also equitable. We can honor the wisdom of those who have lived in harmony with the land and water for thousands of years. It’s time for Western science to step up, listen, and learn.

3. Restoring Ecosystems: Wetlands and Kelp Farming as Pathways to Climate Resilience

Ecosystem restoration is a cornerstone of climate resilience, and two powerful examples emerged from the webinar: the critical role of wetlands and the transformative potential of kelp farming. Wetlands, such as those in the Yucatán Peninsula, act as natural buffers against extreme weather, support biodiversity, and provide essential community resources. However, over 80% of the Yucatán’s wetlands have been lost to natural hazards and human activity, underscoring the urgent need to protect and restore these vital ecosystems. Wetlands are not just environmental assets — they are lifelines for communities, offering flood protection, water filtration, and habitats for countless species.

Similarly, kelp farming and mariculture are emerging as powerful tools for ocean restoration and economic regeneration. Local groups, like the Native Conservancy in Alaska, are leading the way in this space. Kelp farming cleans water, creates habitat for marine life, and provides sustainable food sources, all while sequestering carbon and mitigating climate impacts. Dune highlighted how mariculture empowers coastal communities, particularly women, who make up 60% of new kelp farmers globally. This industry is not just about economic opportunity — it’s about healing the ocean and building regenerative economies that align with Indigenous values of stewardship and reciprocity.

"Appreciate the opportunity to share this space with you today. It has been an honour to hear the words of both speakers and learn from you. Prayers and blessings for your work and peoples." – Cass B., Great Britain

Together, wetlands and kelp farming illustrate the power of nature-based solutions to address climate change and water scarcity. By restoring these ecosystems, we can create resilient communities, protect biodiversity, and honor the Indigenous knowledge that has long understood the interconnectedness of land, water, and life. These practices remind us that the solutions to our environmental crises are not just technical — they are deeply rooted in the wisdom of those who have lived in harmony with nature for generations.

A Call to Action: Learning from the Past to Protect the Future

The webinar underscored a vital truth: the solutions to today’s water and climate crises lie in the enduring wisdom of Indigenous cultures. From decentralized, community-led water systems to the regenerative potential of kelp farming, Indigenous practices offer proven frameworks for sustainability that prioritize reciprocity, resilience, and respect for nature. These approaches, deeply rooted in centuries of observation and stewardship, remind us that effective solutions are not just technical — they are holistic, inclusive, and deeply connected to the land and water.

As we face growing environmental challenges, the call to action is clear: we must listen to and learn from Indigenous peoples, integrate their knowledge into modern systems, and support their efforts to restore ecosystems and build regenerative economies. As Dune powerfully stated, “We are the best we’ve got. I’m in. Are you?”

Meet the Speakers

DR. YOLANDA LÓPEZ-MALDONADO, YUCATÁN, MEXICO

Yolanda López-Maldonado is an Indigenous earth systems scientist working on various aspects of nature conservation. She has a strong background in promoting and defending the diversity of ideas, knowledge, values and forms of self-expression of Indigenous Peoples. Her extensive career encompasses a wide range of topics within both the natural and social sciences, but with a particular focus on including Indigenous sciences and earth observations into contemporary science and policy frameworks.

She has collaborated with both academic and non-academic organizations in multilateral settings at different levels of the United Nations, including UNESCO, IPBES, and CBD. She actively engages in discussions aimed at fostering trust between nations through science and supporting effective policy development.

Recently, she was appointed as the Lead Author for the Indigenous Knowledge and Local Knowledge chapter of the Global Environment Outlook Report 7 by UNEP's Early Warning and Assessment Division. As a Young Scholar at the Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and a Junior Fellow the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Dr. López-Maldonado holds a PhD in Human Geography from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (Germany).

DUNE LANKARD, EYAK ATHABASCAN President & Founder, Native Conservancy

An Eyak Athabascan Native of the Eagle Clan, Dune grew up in Cordova, in southcentral Alaska. His Eyak name is “Jamachakih,” which means "Little Bird that screams really loud and won’t shut up." Born into a fishing family, his life education as a subsistence and commercial fisherman began at age five. He later earned a living as a fishery and processing consultant, as well as a commercial fisherman in the Copper River Delta and Prince William Sound.

When the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred in his backyard of Prince William Sound, Dune had to live up to his Eyak name. He transformed into a social change artist, taking on the powers that be and becoming the Native Rights leader that his mother, Rosie, wanted him to be.

Dune has founded and co-founded numerous non-profit organizations, including the Eyak Preservation Council (EPC), the FIRE Fund (Fund for Indigenous Rights and the Environment), the RED OIL Network (Resisting Environmental Degradation of Indigenous Lands), and the Native Conservancy. His work has helped preserve more than 1 million acres of the Copper River Delta, Prince William Sound, and the Gulf of Alaska region.

He has gained wide recognition, including Time magazine’s Hero of the Planet, as well as fellowships with the Ashoka Foundation, Hunt Alternatives Fund (Prime Movers), Future of Fish, and SeaWeb’s Seafood Champion Award for his tireless OceanBack and LandBack work since 1989.